S P Pandey vividly remembers the night he received a call informing him about a commotion that had ensued near the local river in the Dooars region, a critically important elephant corridor in West Bengal. “The villagers were trying to drive away two elephants on the banks of the river with crackers and shouting,” Pandey explains.

But just as he and his response team reached the site, they were distracted by “boulders bobbing up and down in the water”.

Pandey is the founder of SPOAR (Society for Protecting Ophiofauna and Animal Rights), which collaborates with forest officials, gram panchayats (village governing bodies), and tea estate owners to support human-wildlife coexistence.

Fascination is still rife in Pandey’s voice as he recalls, “While the two elephants were occupying the attention of the village people, a herd of 30 elephants was making its way down the river, trying to safely cross to the other side. Look at how smart these animals are.”

This wasn’t the first time the school teacher had a front row seat to the animal’s ingenuity. His anecdote contextualises the interlinked lives and habits of the ‘endangered’ Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). Poaching, illegal trade, human-elephant conflict, and habitat loss could be blamed for a decline in the species’ numbers, and communities living along elephant territories often bear the brunt of this disruption.

But organisations like SPOAR are attempting to alleviate the pressures on this species. In 2018, Pandey was recognised as a Green Corridor Champion (GCC) by the Wildlife Trust of India.

The Wildlife Trust of India has introduced the Right of Passage initiative directed towards the protection of elephants

As Upasana Ganguly, who heads the ‘Right of Passage’ project at Wildlife Trust of India, explains, the Green Corridor Champions are locals closely involved in protecting elephant corridors with the support of local governments.

Is this model showing success?

“In the Dooars region, we have observed a 60 percent reduction in human deaths and property damage occurring due to human-elephant conflict,” Pandey shares.

Why did the elephant cross the road?

Simple, because humans overlaid their migratory routes with concrete. So now, the question is, how can their routes be revived?

The ‘Right of Passage’ project, instituted in 2005, brought together Wildlife Trust of India, the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands (IUCN-NL), World Land Trust, and UK-based Elephant Family. They worked closely with researchers, officials, and NGOs to identify 88 elephant corridors across India.

The project had a simple goal. “It’s in the name,” says Upasana. “Right of passage implies the right of every large mammal to move from one place to another.” She sets the context for Wildlife Trust of India’s work: “In the early 2000s, much of elephant conservation work was focused on habitats, protected areas, national parks, and sanctuaries. But there was no discussion around the areas elephants move through. There weren’t many interventions outside protected areas.”

Elephant corridors are vital natural pathways that allow herds to move safely between forests, sustaining migration, genetic diversity, and coexistence with human landscapes.

With rising urbanisation and industrialisation, the gentle giants were caught between the blurring boundaries of the mainland and the hinterland.

To this end, the Right of Passage project intended to identify, map, and protect the strips of land that elephants use to move from one habitat to another. Known as elephant corridors, these pathways are crucial, as a lack of them could orphan the animals from their natural routes, leading to demographic isolation and possible extinction.

But accurately delineating the boundaries of an elephant corridor comes with its own set of challenges. This is where the Wildlife Trust of India devised a unique approach. “A lot of connectivity studies happen using satellite imagery or GI space modelling; elements and variables are entered, and that’s how corridors are identified,” Upasana explains. But these remain estimates.

Wildlife Trust of India engages communities and children to spread awareness around elephants and their ecological importance.

Instead, she says Wildlife Trust of India’s studies are completely based on teams venturing into these fragile intersections. “We visit the sites, follow the same paths as an elephant moving from one habitat to another, and note down everything: the barriers an elephant may be facing, the possibilities of conflict situations, and upcoming threats.” Once a corridor is identified, the next step is protection.

Right of passage

India’s elephant population currently stands at 22,446. In 2017, the population was 27,312.

With their natural habitats shrinking due to human encroachment, protecting migratory routes has become all the more important. The Right of Passage project, in collaboration with the Government of India’s Project Elephant (a conservation initiative launched in 1992) and state forest departments, does not just focus on helping the animals manoeuvre safely by protecting their corridors, but also on strengthening coexistence between elephants and humans.

The Right of Passage project focuses on on strengthening coexistence between elephants and humans.

Upasana explains, “Most of our efforts between 2002 to 2017 were focused on three models: private purchase, government acquisition, and community securement.”

These revolved around setting aside land for elephants, albeit by mobilising different players. The private purchase model meant directly purchasing the land, rehabilitating local people, and then handing over the land to the relevant state forest department for legal protection; the community securement model hinged on benefit-sharing with communities, while the government acquisition model provides national and state governments with technical assistance for the acquisition of key corridors.

Despite these models, elephant corridors were being impaired. “There was no movement of elephants happening in some of these areas because of industrial or settlement expansion. So the elephants were figuring out other ways of moving. But that was leading to more conflict,” Upasana shares.

She adds, “So, we realised that while we were identifying and mapping the corridors, there was no one to keep an eye on them, and that’s where the concept of Green Corridor Champions came up.”

Pandey is one such example. This led to the fourth model, the public securement model, through which local stakeholders are empowered to safeguard corridors.

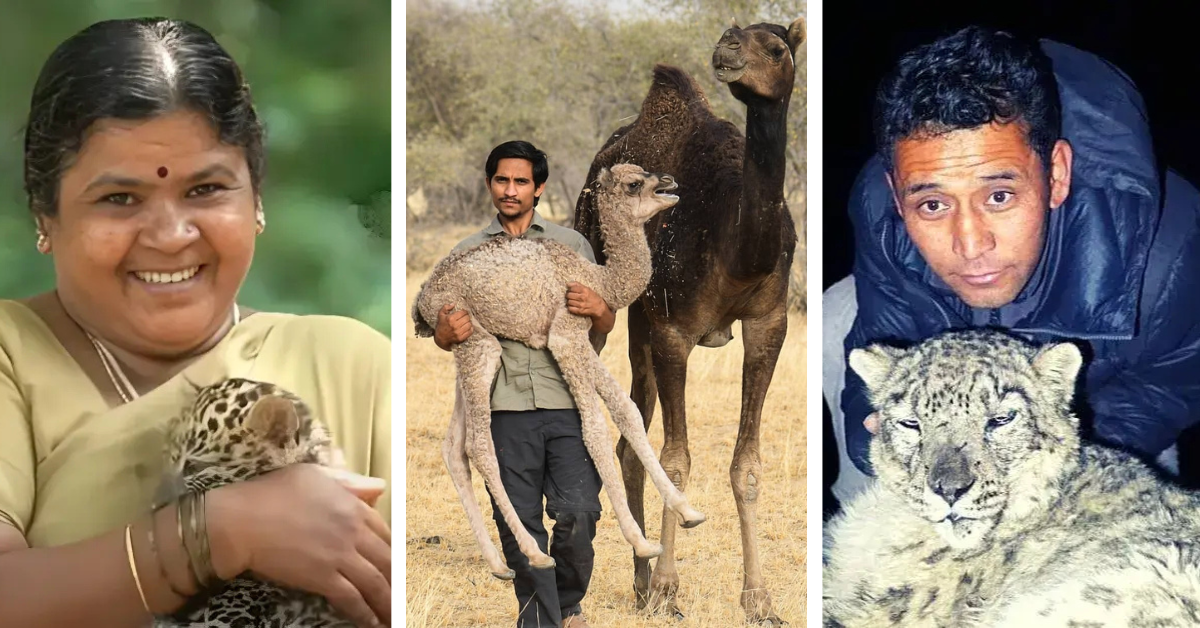

The community securement model introduced by Wildlife Trust of India is premised on benefit-sharing with communities. Photograph: (Arindam Ghatak)

Currently, Upasana shares that Wildlife Trust of India has 30 such partnerships. “These are people from different backgrounds, living in proximity to these corridors, who may already be doing some wildlife conservation work. They have three primary responsibilities. The first is monitoring corridors to assess how elephants use them and whether their functionality is intact. This includes tracking existing threats and barriers to movement, and engaging in dialogue with forest departments. If a road, railway expansion, or highway is proposed, we can intervene early.”

She adds that the second includes community awareness events with school children, youth, and college students, while the third is catalysing local policy actions. “Many of our GCCs are quite influential in their own way. So they can probably arrange for meetings with authorities whenever there is a coordination gap between different agencies.”

The four-model approach has yielded successful results, with the Wildlife Trust of India’s mapped corridors standing at 101. The aim isn’t just to ensure the gentle giants have access to their migratory routes, but that as they do so, it doesn’t come at a cost to communities.

This story is part of a content series by The Better India and Wildlife Trust of India.

All pictures courtesy Wildlife Trust of India