The study, released on Monday, ahead of G20 meetings taking place later this month in Johannesburg, South Africa, shows that unequal access to housing, healthcare, education and employment leaves millions more exposed to disease.

The report launched by UNAIDS – the global body’s agency dedicated to ending AIDS and HIV infection – finds inequality is not only worsening the spread and impact, but also undermining global capacity to prevent and respond to outbreaks.

Breaking the inequality–pandemic cycle: building true health security in a global age, calls for a fundamental shift in what we mean by “health security.”

Vicious cycle

The new data shows pandemics increase inequality, fuelling a cycle that is visible not just in the aftermath of COVID-19, but also for AIDS, Ebola, Influenza, mpox and beyond.

Co-chaired by Nobel Laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz, former First Lady of Namibia Monica Geingos, and leading epidemiologist Professor Sir Michael Marmot, the Global Council on Inequality, AIDS and Pandemics – which carried out the research – has a stark conclusion: pandemics and inequality are locked in a vicious cycle, each feeding the other in ways that threaten global stability and progress.

“Inequality is not inevitable. It is a political choice, and a dangerous one that threatens everyone’s health,” said Ms. Geingos. “Leaders can break the inequality–pandemic cycle by applying the proven policy solutions in the Council’s recommendations.”

Global inequalities exacerbate risks

Studies reviewed by the Council reveal that unequal access to housing, education, employment and health protection created conditions in which COVID-19, AIDS, Ebola and Mpox spread faster and hit hardest.

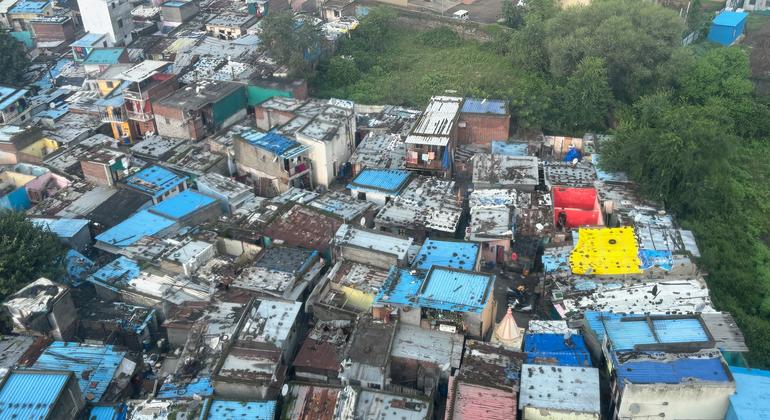

For example, people living in informal settlements in African cities were found to have higher HIV prevalence than those in formal housing. In England, overcrowded housing was associated with higher COVID-19 mortality.

In Brazil, people without basic education were several times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those completing elementary school.

The Mathare slum in Nairobi houses 500,000 people within 5 square kilometres.

Between countries, global inequalities exacerbate shared risks. Low-income countries have faced repeated obstacles in accessing vaccines, medicines and emergency financing, leaving outbreaks uncontrolled and prolonging global disruption.

“The evidence is unequivocal,” said Professor Marmot. “If we reduce inequalities, through decent housing, fair work, quality education and social protection, we reduce pandemic risk at its roots.”

Towards true health security

UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima, said the findings come at a pivotal moment as the G20 meets under South Africa’s presidency.

“This report shows why leaders urgently need to tackle the inequalities that drive pandemics, and it shows them how they can do this,” Ms. Byanyima said.

© WHO/Arete/Florion Goga

Pensioner Xhane Grodani who lives with her husband in Tirana, Albania, receives her third COVID-19 vaccination at a clinic in the capital.

“Reducing inequalities within and between countries will enable a better, fairer and safer life for everyone,” she added.

The report aligns with South Africa’s G20 theme of “Solidarity, Equality, Sustainability”, highlighting that achieving genuine health security will depend on economic justice and social equity as much as on vaccines or laboratories.

The Global Council outlines four key actions to break the “inequality–pandemic cycle”:

- Removing financial barriers to ensure all countries have the fiscal space to tackle inequality.

- Investing in the social determinants of health, such as housing, nutrition, education and employment, to reduce vulnerability to disease.

- Guaranteeing equitable access to pandemic-related technologies by treating research and innovation as global public goods and promoting regional production.

- Strengthening community-led, multi-sectoral responses by embedding pandemic preparedness within local systems and ensuring broad participation across government, civil society and science.